Heaven’s Ledger: Orbital debris as modern parable—forty-two-thousand nine-hundred forty-one objects tell a story of intent vs. entropy.

Our Gods Haven’t Fallen, Yet

A Space Junkies’ Riddle — Our Cathedral

Tony O’Connor Critical Infrastructure Protection Specialist

January 2026 | historiesrawtruth.com

“I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven.” — Luke 10:18

SYMBOLS GUIDE

Before we begin, here are the symbols you’ll encounter. Each is explained again where it first appears.

| Symbol | Name | Pronunciation | What It Means |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Population count | “en” | The number of objects in a system |

| N² | N-squared | “en-squared” | N multiplied by itself. Governs how fast risk grows. |

| P | Pairs | “pee” | Number of possible collision pairs |

| β | Beta | “bay-tah” | Ballistic coefficient. Low β = falls fast. High β = falls slow. |

| v | Velocity | “vee” | Speed. Orbital velocity ≈ 7.6 km/s (17,000 mph). |

| v² | Velocity squared | “vee-squared” | Speed × speed. Drag force scales with this. |

| ρ | Rho | “row” | Air density. At 550 km: ~10⁻¹² kg/m³ (almost nothing). |

| F_d | Drag force | “eff-sub-dee” | How hard air pushes on a satellite. |

| C_d | Drag coefficient | “see-sub-dee” | Shape factor. ~2.2 for a flat satellite. |

| A | Area | “ay” | Cross-sectional area (face size). ~8–10 m² for Starlink. |

| m | Mass | “em” | Weight. ~260 kg for Starlink. |

| kg | Kilogram | “kill-oh-gram” | Unit of mass. About 2.2 pounds. |

| km | Kilometer | “kill-oh-meet-er” | 1,000 meters. About 0.62 miles. |

| m² | Square meters | “meters squared” | Area measurement. |

| kg/m² | Kilograms per square meter | “kilograms per meter squared” | How β is measured. |

| ~ | Approximately | “about” | Not exact, but close enough. |

| ≈ | Approximately equal | “approximately equals” | Nearly the same value. |

READING SCIENTIFIC NOTATION

Numbers in this article sometimes use powers of ten. Here’s how to read them:

Big numbers (positive powers):

- 10³ = 1,000 (one followed by 3 zeros)

- 10⁶ = 1,000,000 (one million)

- 10⁹ = 1,000,000,000 (one billion)

Small numbers (negative powers):

- 10⁻³ = 0.001 (decimal point, 2 zeros, then 1)

- 10⁻⁶ = 0.000001 (one millionth)

- 10⁻¹² = 0.000000000001 (one trillionth)

Combined expressions:

- 2.4 × 10⁶ = 2,400,000 (2.4 million)

- 1.5 × 10⁻¹² = 0.0000000000015

The trick: The exponent tells you how many places to move the decimal. Positive = right (bigger). Negative = left (smaller).

THE CATALOG: WHAT’S UP THERE

Imagine 42,941 metal ghosts circling Earth at 17,000 mph—14,707.6 tons of consequence in motion (ESA, 2025).

Most are dead:

- 13,575 fragmentation shards from old collisions

- 10,873 pieces too small or tumbling too fast to identify

- 2,051 spent rocket bodies—empty shells from past launches

- 1,160 mission-related objects—lens caps, deployment mechanisms, bolts

Only 8,561 Starlinks still hum with purpose, beaming internet to Earth (JSR, 2025). The rest are debris. Consequences of launches we didn’t plan exits for.

And that’s just what we can track. Below the 10 cm threshold:

- ~1.2 million objects between 1–10 cm

- ~140 million particles between 1 mm and 1 cm

At 17,000 mph, a 1 cm fragment hits with the energy of a hand grenade.

THE PHYSICS: WHY SATELLITES FALL

Physics pulls them down. Every satellite has a ballistic coefficient—call it β—measuring how much the ghost-thin air drags on it. For a Starlink, β ≈ 12–15 kg/m². That means it loses 0.4–1.5 kilometers of altitude per day at 550 km. When the Sun burped in February 2022—a geomagnetic storm that thickened the upper atmosphere by 50–125%—38 fresh Starlinks couldn’t climb. They burned within days (AGU, 2022).

Why does thin air matter at orbital speed? Because drag scales with velocity squared. At 17,000 mph, even a few molecules hit hard. The whisper becomes a roar.

Let’s unpack the equations so you can see exactly how this works.

Equation 1: The Drag Force

F_d = ½ρv²C_dA

This calculates how hard the air pushes against a satellite.

Breaking it down piece by piece:

| Symbol | What it means | Starlink example |

|---|---|---|

| F_d | Drag force (Newtons) | What we’re calculating |

| ρ | Air density (kg/m³) | ~10⁻¹² at 550 km |

| v | Velocity (m/s) | 7,600 m/s |

| v² | Velocity squared | 57,760,000 |

| C_d | Drag coefficient | ~2.2 |

| A | Cross-sectional area (m²) | ~10 m² |

| ½ | One-half | 0.5 |

Order of operations (step by step):

- Square the velocity:

- 7,600 × 7,600 = 57,760,000 m²/s²

- Multiply by air density:

- 57,760,000 × 0.000000000001 = 0.00005776

- Multiply by drag coefficient:

- 0.00005776 × 2.2 = 0.000127

- Multiply by area:

- 0.000127 × 10 = 0.00127

- Multiply by one-half:

- 0.00127 × 0.5 = 0.000635 Newtons

What does 0.000635 Newtons feel like?

About the weight of a small ant sitting on your hand. Tiny. Almost nothing.

But here’s the thing: that tiny force acts continuously, hour after hour, orbit after orbit. Over days and weeks, it accumulates. The satellite slows down. When it slows down, it falls. When it falls, the air gets thicker. When the air gets thicker, the drag gets stronger. The process accelerates itself.

The child’s version: Imagine running through fog. Fog is almost nothing—you can barely feel it. But if you ran at 17,000 mph, that almost-nothing would hit you like a wall. That’s why v² matters. Speed times speed turns thin air into drag.

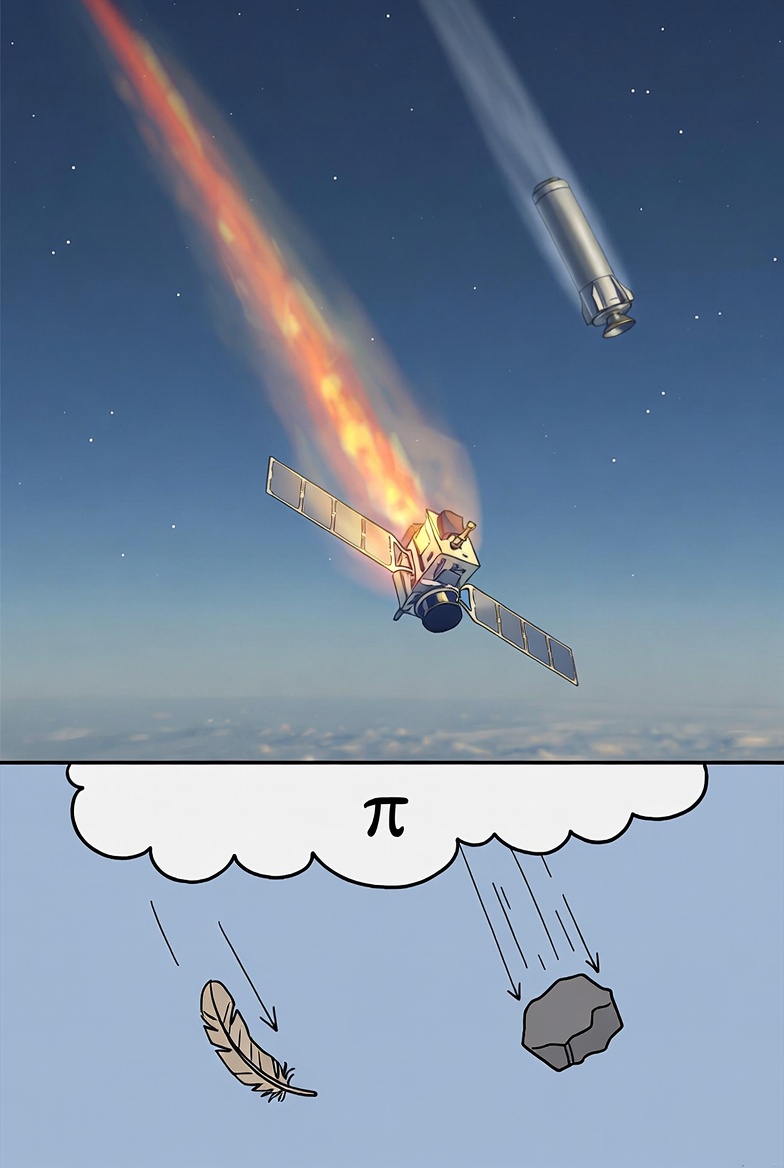

Equation 2: The Ballistic Coefficient

β = m / (C_d × A)

This tells us whether a satellite falls like a feather or a rock.

Breaking it down:

| Symbol | What it means | Starlink example |

|---|---|---|

| β | Ballistic coefficient (kg/m²) | What we’re calculating |

| m | Mass (kg) | 260 kg |

| C_d | Drag coefficient | 2.2 |

| A | Area (m²) | 10 m² |

Order of operations:

- Multiply drag coefficient by area:

- 2.2 × 10 = 22 m²

- Divide mass by that result:

- 260 ÷ 22 = ~12 kg/m²

What does the number mean?

| β value | Behavior | Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Low (~12 kg/m²) | Light for its size. Air catches it. Falls fast. | Feather |

| Medium (~50 kg/m²) | Balanced. Falls at moderate rate. | Leaf |

| High (~100+ kg/m²) | Heavy for its size. Plows through air. Falls slow. | Rock |

Starlinks have low β by design. They’re flat and light. If one dies, it falls fast and burns up quickly. That’s good engineering—dead satellites should become shooting stars, not permanent hazards.

Old rocket bodies have high β. They’re heavy cylinders that plow through the thin air slowly. They can stay up for decades. That’s the debris problem.

The child’s version: Drop a feather and a rock from the same height. The feather floats down slowly because air catches it. The rock plummets because its weight wins against the air. β tells you whether a satellite is more feather or more rock.

Equation 3: Decay Rates

How fast does a satellite fall? It depends on altitude and solar activity.

At 550 km altitude (Starlink operational height):

| Condition | Air density | Decay rate | Time to reentry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solar minimum | ~10⁻¹² kg/m³ | 0.4 km/day | ~3–4 years |

| Normal | ~2×10⁻¹² kg/m³ | 0.8 km/day | ~2 years |

| Solar maximum | ~4×10⁻¹² kg/m³ | 1.5 km/day | ~1 year |

| Storm (Feb 2022) | ~5×10⁻¹² kg/m³ | >1.5 km/day | Days |

Why does solar activity matter?

The Sun heats Earth’s upper atmosphere. When the Sun is active (storms, flares, coronal mass ejections), the atmosphere expands and gets thicker at orbital altitudes. Thicker air = more drag = faster decay.

The February 2022 storm increased air density by 50–125%. Normal insertion would have worked. Storm conditions made it impossible.

The order of decay (how falling accelerates):

- Satellite at 550 km loses ~0.8 km/day

- At 400 km, it loses ~2–3 km/day (air thicker)

- At 300 km, it loses ~5–10 km/day

- At 200 km, it loses ~20+ km/day

- Below 150 km: terminal descent, burns up in hours

Decay is a one-way ratchet. Once it starts accelerating, there’s no going back without propulsion.

Equation 4: N² Scaling (The Scary One)

P = N(N-1)/2 ≈ N²/2

This calculates the number of possible collision pairs among N objects.

Order of operations:

- Start with N objects (satellites in orbit)

- Subtract 1: Each object can pair with N-1 others

- Multiply: N × (N-1) gives total directional pairings

- Divide by 2: Each pair counted twice (A-B is same as B-A)

Example with 10 satellites:

- N = 10

- N – 1 = 9

- 10 × 9 = 90

- 90 ÷ 2 = 45 possible collision pairs

Example with 100 satellites:

- N = 100

- N – 1 = 99

- 100 × 99 = 9,900

- 9,900 ÷ 2 = 4,950 possible collision pairs

Ten times the satellites. One hundred times the pairs.

The scaling table:

| Satellites (N) | Collision pairs | Growth factor |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 45 | — |

| 100 | 4,950 | 110× |

| 1,000 | 499,500 | 100× |

| 10,000 | 49,995,000 | 100× |

| 100,000 | 4,999,950,000 | 100× |

The trap: Your brain naturally thinks “10× more satellites = 10× more risk.” That’s linear thinking. Reality compounds quadratically: “10× more satellites = 100× more collision pairs.”

We reason additively. The universe multiplies.

The child’s version: Imagine a party. With 2 guests, there’s 1 possible handshake. With 4 guests, there are 6 handshakes—not 2, not 4, but 6. With 10 guests, there are 45 possible handshakes. Double the guests doesn’t double the handshakes. It roughly quadruples them. Every person you add doesn’t just add themselves—they add potential connections with everyone already there.

Satellites work the same way. More satellites = way more chances to hit each other.

THE EVENT: FEBRUARY 2022

On February 3, 2022, SpaceX launched 49 brand-new Starlink satellites. Everything nominal. Systems check-out. Ready to climb to operational altitude at 550 km.

Then the Sun burped.

A geomagnetic storm (Kp index ≈ 5, moderate severity) hit Earth on February 3–4. The storm heated the thermosphere, causing it to expand. Air density at 210 km—the satellites’ insertion altitude—increased by 50–125% above normal (Fang et al., 2022).

The numbers:

| Parameter | Normal | During storm |

|---|---|---|

| Air density at 210 km | ~10⁻¹⁰ kg/m³ | ~1.5–2.25 × 10⁻¹⁰ kg/m³ |

| Drag force | Baseline | 50–125% higher |

| Climb capability | Sufficient | Insufficient |

That’s still almost nothing in absolute terms. But remember v²—at 17,000 mph, “almost nothing” becomes “enough to matter.”

What happened:

The 49 satellites were inserted at ~210 km altitude and immediately began raising their orbits using onboard ion thrusters. Under normal conditions, this works fine—the thrust overcomes drag, and they climb to 550 km over several weeks.

Under storm conditions, drag exceeded thrust. The satellites couldn’t climb. They couldn’t even hold altitude. They fell.

Within 5 days, 38 of the 49 satellites burned up in Earth’s atmosphere.

The lesson:

Physics worked exactly as the equations predict. SpaceX didn’t make an error—they made a bet on normal conditions, and the Sun called it. The whisper became a roar. The math bit back.

THE THREAT: KESSLER SYNDROME

By 2030, constellation plans could put 100,000 satellites in orbit. Collision risk scales quadratically—N² means doubling the population roughly quadruples the collision pairs. Cross a threshold, and Kessler Syndrome begins: collisions breed debris, debris breeds collisions, cascading until orbits become unusable for 50–100 years.

In 1978, NASA scientist Donald Kessler calculated something uncomfortable.

The cascade mechanism:

- Two satellites collide

- Collision creates thousands of fragments

- Fragments spread into intersecting orbits

- Each fragment can cause another collision

- Each new collision creates more fragments

- Debris generation exceeds natural removal

- Chain reaction becomes self-sustaining

The math:

- Today: ~14,000 active satellites → ~98 million collision pairs

- 2030: ~100,000 satellites → ~5 billion collision pairs

- Growth: ~50× more pairs in 5 years

At some threshold (exact value debated, but we’re approaching it), the cascade becomes inevitable.

The timeline:

| Phase | Duration | What happens |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger | Minutes | Initial collision |

| Cascade | Hours to months | Fragment cloud expands, secondary collisions |

| Lockout | 50–100 years | Debris density too high for safe operations |

| Recovery | Centuries | Natural atmospheric drag slowly clears fragments |

The consequence:

- GPS dark (navigation, timing, precision agriculture)

- Weather satellites blind (hurricane tracking degraded)

- Communication severed (satellite internet, remote connectivity)

- Aviation scrambling (backup navigation systems overloaded)

- Military readiness compromised

Not a temporary inconvenience. A generational lockout. Children born today would retire and die before our skies reopen.

THE GOVERNANCE GAP

Governance is asymmetric. The FCC’s 5-year deorbit rule (2024) binds U.S. operators. Everyone else operates under voluntary guidelines—IADC recommendations, UN COPUOS principles (2019). One nation enforces. The rest hope. Hope doesn’t deorbit satellites.

Binding (U.S. only):

| Rule | Requirement | Enforcement |

|---|---|---|

| FCC 5-Year Rule (2024) | U.S. satellites must deorbit within 5 years of mission end | License revocation, financial penalties |

Voluntary (everyone else):

| Framework | Recommendation | Enforcement |

|---|---|---|

| IADC Guidelines (2025) | 25-year deorbit, debris mitigation | None |

| UN COPUOS Principles (2019) | 21 sustainability guidelines | None |

| ESA Zero Debris Charter | Net-zero debris by 2030 | Voluntary pledges |

The gap:

One nation has binding rules. The rest operate on good intentions. But intention without enforcement is aspiration, not governance. The satellites that will cause Kessler Syndrome aren’t necessarily American satellites.

THE TECHNOLOGY: WHAT WE COULD DO

The technology exists: design for demise, phased rollouts, active debris removal. ESA’s Draco mission (2025) demonstrated cleaner controlled reentry. The gap isn’t capability. It’s intention—the directed will to implement what we already know works.

Design for Demise: Build satellites from materials that burn up completely on reentry. No surviving fragments to hit the ground or remain in orbit.

Passivation: At end of mission, drain fuel tanks, discharge batteries, safe pressure vessels. Prevent explosions that create debris clouds.

Active Debris Removal: Capture dead satellites and drag them down.

- Nets and harpoons (proven in tests)

- Robotic arms (ClearSpace-1, launching 2026)

- Laser ablation (theoretical, but promising)

- Ion-beam shepherd (uses exhaust to push debris)

Phased Constellation Deployment: Don’t launch 10,000 satellites at once. Build up gradually. Monitor conjunction rates. Adjust if cascade indicators rise.

Better Tracking: Extend radar/optical networks. Track objects below 10 cm. Share data internationally.

The solutions exist. We know how to do this. ESA’s Draco mission proved controlled deorbit works. SpaceX deorbits ~12 old Starlinks per week—intentionally, safely.

The gap isn’t capability. It’s intention.

THE QUESTION

Whose hand pushes satellites earthward?

Physics does the pulling. Gravity and drag are automatic. They don’t ask permission. They don’t negotiate. They work exactly as the equations predict—every time, for every object, without exception.

But we chose to launch 42,941 objects without planning how most of them would come down. We chose speed over stewardship. We chose convenience over consequence. We chose profit today over access tomorrow.

The technology to do this right exists. The governance frameworks exist, at least in voluntary form. What’s missing is the directed will to implement what we already know works.

THEOLOGICAL REGISTER

This section is isolated from the empirical claims above. The physics stands independent of any reader’s theological commitments. What follows is reflection, not evidence.

The epigraph from Luke 10:18—”I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven”—resonates with the descent imagery throughout this document. Satellites falling. Debris cascading. Systems crashing. Lightning-fast consequences of hubris.

The empirical answer to why satellites fall is physics: drag equations, ballistic coefficients, v² scaling. We didn’t design these laws; we discovered them.

But we did design the satellite constellations. We did choose the orbits. We did decide to launch without planning exits.

The stewardship question isn’t whether the physics is true—it is. The question is whether we tend the garden or trash it. Whether we’re stewards of the orbital environment or just the latest species to foul its own nest.

Dominion was given. Stewardship was implied. We’re choosing, right now, which one we mean.

That question belongs to a different register—one this document acknowledges but does not confuse with the math.

EQUATION SUMMARY

| Equation | What it calculates | Child version |

|---|---|---|

| F_d = ½ρv²C_dA | How hard air pushes on a satellite | Running through fog at 17,000 mph |

| β = m/(C_dA) | Whether it falls like feather or rock | Feathers float, rocks plummet |

| P = N(N-1)/2 | How many collision pairs exist | Handshakes at a party |

SOURCES

- European Space Agency. Space environment statistics. September 2025. sdup.esoc.esa.int

- Jonathan’s Space Report. Active satellite statistics. October 2025. planet4589.org

- Fang, F. et al. “The February 2022 Starlink storm: Impacts of a geomagnetic storm on low Earth orbit satellites.” Space Weather, AGU, 2022.

- Kessler, D.J. & Cour-Palais, B.G. “Collision frequency of artificial satellites: The creation of a debris belt.” Journal of Geophysical Research, 1978.

- Federal Communications Commission. “Space innovation; mitigation of orbital debris in the new space age.” Federal Register, Document 2024-17093, August 2024.

- UN COPUOS. Long-term sustainability guidelines. 2019.

- Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee. Space debris mitigation guidelines (Rev. 4). 2025.

DOI

Original publication: 10.5281/zenodo.17355854

The math never asked for forgiveness. The scalar doesn’t breathe. It exhales. Once.

Tony O’Connor Critical Infrastructure Protection Specialist

historiesrawtruth.com | tonyoconnor17.substack.com | @tonyoconnor_

January 2026

© 2026 Tony O’Connor. All rights reserved.

Full riddle: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17835722

Notes:

– **DOI**: O’Connor, T. (2025). Our Gods Haven’t Fallen, Yet — A Space Junkies’ Riddle — Our Cathedral. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17835722.

– **License**: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 added, aligning with no-remixing restriction under copyright.

Originally posted to X on October 15, 2025, this publication precedes our Historiesrawtruth.com and, thus, precedes our “Hello World.” It is maintained here for posterity and edification.

No Responses